For most people, the idea of frozen ground typically conjures up ideas about winter weather and the occasional hard frost. But in many parts of the world, frozen ground is a year-round phenomenon and an everyday part of life.

A distinct characteristic of high latitudes, perennially frozen ground is otherwise known as permafrost, and near-continuously underlies significant northern regions of Alaska, Canada and Russia (as much as 25% of northern hemisphere land area).

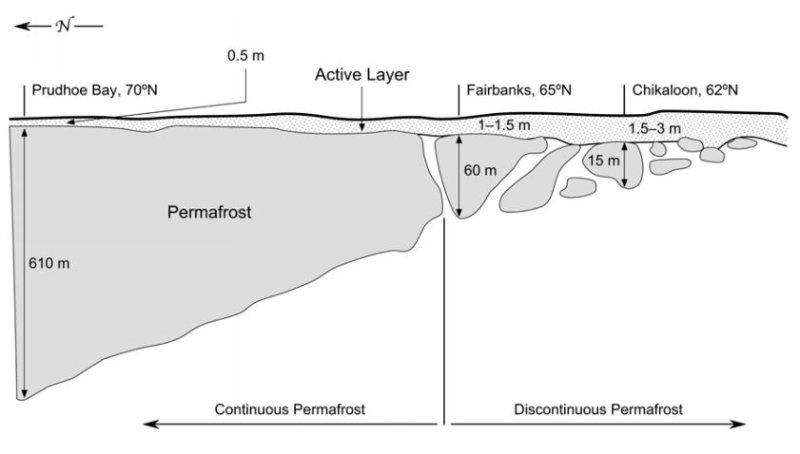

Current distribution of northern hemisphere permafrost

In a warming climate, primary effects on permafrost are a thickening of the active layer which is the surficial seasonal thaw depth that becomes unfrozen in the warmer months of the year, and an increase in talik frequency; taliks are sub-surface gaps with reduced or no ground ice in continuous and fringe permafrost zones.

Other more dramatic changes are consistent with thermokarst development, slope instabilities and slope failures, as well as changes in hydrologic drainage patterns.

Depiction of relative permafrost thickness by latitude in Alaska

Current and projected changes in permafrost characteristics and distribution have potential wide-ranging effects, but the effects on existing infrastructure, as well as engineering and construction practices going forward need significant consideration.

- Building Foundations and Other Infrastructure

- Buildings and other infrastructure can conduct heat into underlying permafrost. When not accounted for through use of extensive insulation, blow-through spaces, and/or use of thermosyphons, structures can experience settling under the foundation often resulting in permanent damage; rendering the structure unusable.

- Highways and Transportation Routes

- Similar to buildings, roadways can conduct heat into underlying permafrost causing differential settlement and heave along a given transportation route. Significant repair costs and routine maintenance are required to keep these routes operational.

- New ‘Hang-Fire’ on Existing Infrastructure

- In mountainous regions, changes in permafrost characteristics can decrease slope stability thereby increasing slope failure hazard and the likelihood of rapid mass movements.

- Flooding and Dynamic Water Drainage

- Thermokarst developments can propagate across large areas and reroute seasonal water drainage, resulting in flood hazards that were not previously a concern. Small, localized drainage changes can also cause problems for infrastructure foundations if not handled properly.

- Mine Tailings and Tailings Dams

- Tailings dams built in permafrost regions may need significant retrofits as these structures become increasingly unstable due to changes in local and regional permafrost tables. Dam failures, aside from heavy flooding, can release harmful contaminants into fragile watersheds and incur high remediation costs.

- Logistics and Remote Access

- Winter work seasons are shortening, leaving a smaller time window for resource exploration in arctic regions (see a previous post on northern Ice Roads) Additionally, over-summering of drill-rigs and other temporary infrastructure may need special design considerations to counter heavy environmental impacts. Lastly, access to high value resource extraction sites may see higher maintenance requirements on primary access routes; contingencies may need to be considered with potential landscape-scale changes.